|

A Guide to Implementing the Theory of

Constraints (TOC) |

|||||

|

Deming |

Taylor & Social Darwinism |

Toyota, Kaizen, & Lean |

|

|

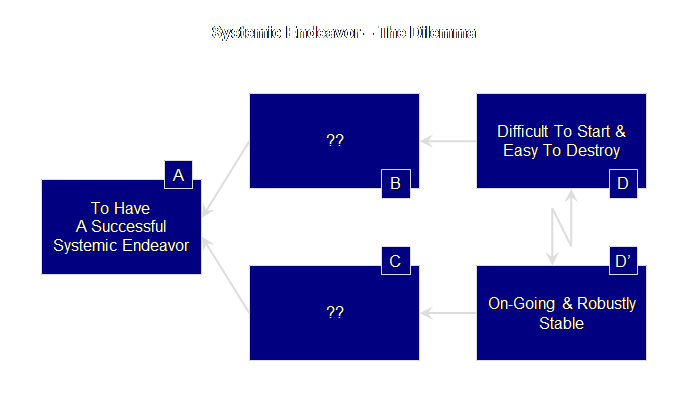

Introduction There is a paradox

afoot that I will call the paradox of systemism. All of our systemic endeavors suffer from

this paradox, and all of our human endeavors are systemic at their

roots. That is to say all of our human

endeavors are to do with the social whole rather than the individual parts,

and regardless of what we as individuals may think, we are social

animals. My own experience within

Theory of Constraints; borne directly from my implementations, indirectly

from countless interactions with others, and the historical perspective of

the preceding pages in this section, convinces me of the prevalence of this

issue. The paradox

can be expressed as follows; Ø

How

is it that a systemic endeavor once established is on-going and robustly

stable, and yet so difficult to start and also so easy to destroy? To that

statement I would only like to add “apparently so difficult to start,” but I

am getting ahead of myself. What then

are the pre-requisites that give rise to this situation? Of course in a

“blink” I can tell you the reason for how

this is – it is a result of the application of our own common sense, our

so-called common wisdom. That is,

common sense is the cause of the paradox.

But to explain to you the reason why

this happens will take the remainder of the page. And is there a solution to the paradox? Well, yes there is. The solution is a particular mix of; skill,

rational knowledge, and experience – a rather uncommon experience, an expertise

actually – but in no sense restricted or unobtainable. It is exposure to, and assimilation of, the

uncommon rational knowledge, that enables us to first gain, and then to

internalize, the necessary uncommon experience, the necessary uncommon

expertise. I want to explain this in three stages. The first stage is something that we now

“know” and accept as true, but which still, if we are honest, confounds ours

senses – the Copernican Revolution – the fact that the earth moves around the

Sun and around its own axis too. I

want to address the broader issue of learning through this example of the

Copernican Revolution. The Copernican

Revolution in its historic context was as paradigmal then as is any current

systemic, or organizational, or industrial process today, in fact much more

so. Once we have established the story

and the logic for the Copernican Revolution, then we can then port the logic

to develop the case for systemic industrialization, using the broader issue

of managing via the Theory of Constraints as the example. This is the second stage. The third stage returns to the starting

question, the paradox a systemism, and answers it explicitly for the first

time, although by then we will have seen this happen twice already. You will know the answer before we get

there. The three stages are tied

together; firstly by a consistent logic, and secondly by our own individual

need for our sense of identity. You may not wish to know this, but let me

tell you anyway, this is abductive logic.

The three stories, the three explanations, share the same structure,

or rather the same logic, but differ in the details. Abductive logic is important to me. The cloud is a superb example of this type

of logical structure appearing in the same way in different narratives, in

fact allowing us to make sense of apparently different narratives, and it is

the cloud that we will use to illustrate this process. In my earlier iterations of this page I told

this story to completion without the use of clouds. That was in part to overcome the resistance

of those for whom clouds are something to react against. For some people the message is lost in

their reaction to the medium. I no

longer wish to accommodate those who do not wish to make any effort. Some people react simply to avoid the

responsibility that they can see staring them down. If we don’t each develop our own individual

skill for using clouds then we won’t succeed in this transformation. Clouds were born out of necessity, they are

not “nice to haves” they are “need to haves,” otherwise we are forever locked

in a local conflict with no way out. Indulge me for a moment longer. The two “base” clouds that you are going to

see; about learning and the Copernican Revolution, and about managing and the

Theory of Constraints, have a special structure. I will return issues around that structure

towards the end, but for now I just want you to be aware that the “B” entity

is a “subset” or local need, and the “C” entity is a “set” or global

need. As these two clouds unfold you

will see they share a commonality.

This commonality is productive in numerous other clouds once you learn

to use it. Some other “rules” will

fall out as we proceed, and you will find a lot more in the Advanced Section

on the mechanics of clouds. I had to

decide a cut-off, or else we will be here all day, there is much productive

work to be done, but this page was intended to be the last page of (this part

of) the website, and that is the way it should remain. So I’ve pretty

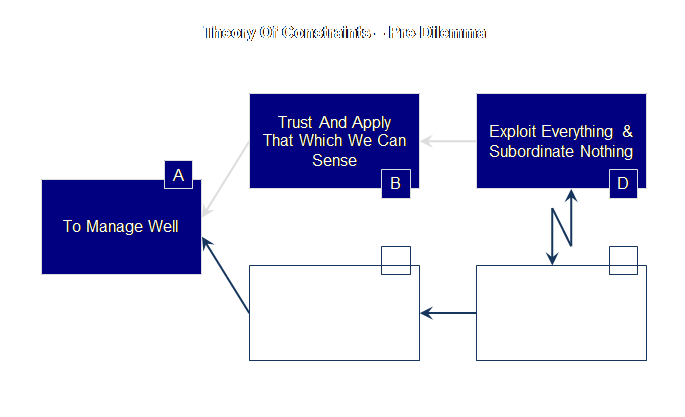

much let the cat out of the bag, we can draw this simple paradox, the paradox

of systemism as a cloud, so let’s do that first – partially complete at least

– and then we will examine the issues around learning and the Copernican

Revolution, then managing and the Theory of Constraints, and then come back

and complete the missing parts of this cloud.

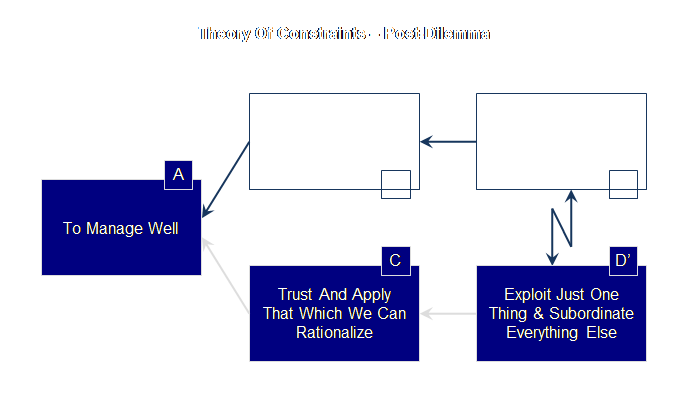

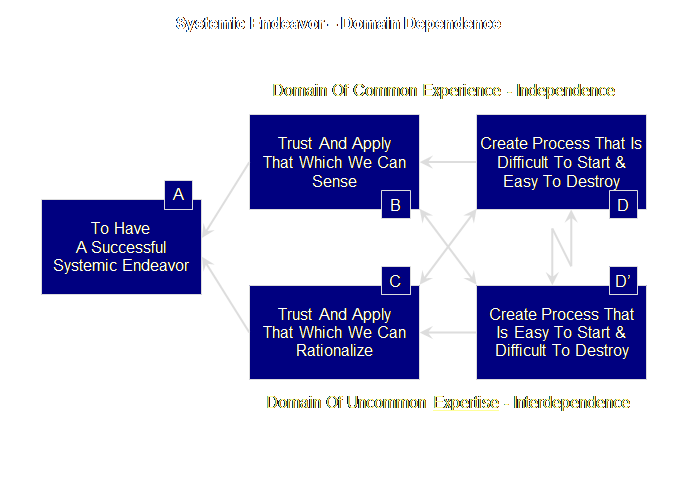

In this cloud there are two mutually exclusive states. One state, the upper arm, is the state of

non-systemism, the state of local optimization. For most people this is also the current

state, and our undesired state, where we have difficulty starting our

systemic endeavors and no difficulty in destroying them. It is what we do have and don’t want.

Now let’s be just a little more particular. The two arms of the cloud, or rather the

two “wants” of the cloud, should be mutually exclusive, and preferrably

opposites of each other – otherwise we might simply oscillate between the

two. The upper arm is about the

beginning and the end – undesirable as it is – whereas the lower arm is about

the middle – desireable as it is.

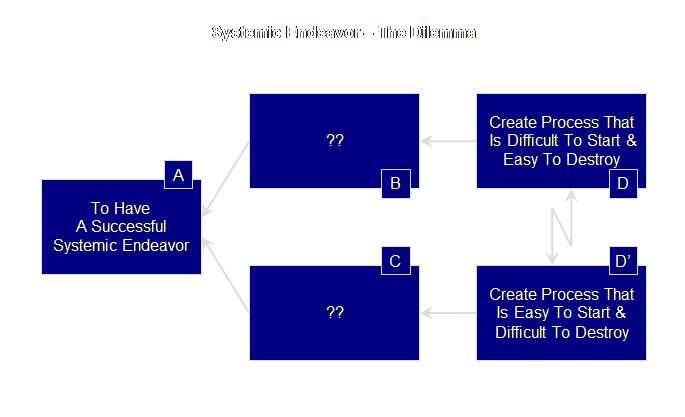

Well, in this game it is often necessary to say what we really mean so

I will reword the cloud a little differently from the formulation of the

original written paradox that we started out with. Additional clarity will not hurt. Let’s have a look.

Before we leave this partially completed cloud, note also how I have

kind of “twisted” the two entities or the two subparts of each entity. The

upper one reads “difficult to start and easy to destroy” and the lower one is

reversed to “easy to start and difficult to destroy.” It seems a feature to me of many paradigmal

clouds that there is often a two-foldedness about the contents of the entity

in conflict. I don’t know if that is a

hard and fast rule, but it certainly seems common and I would encourage you

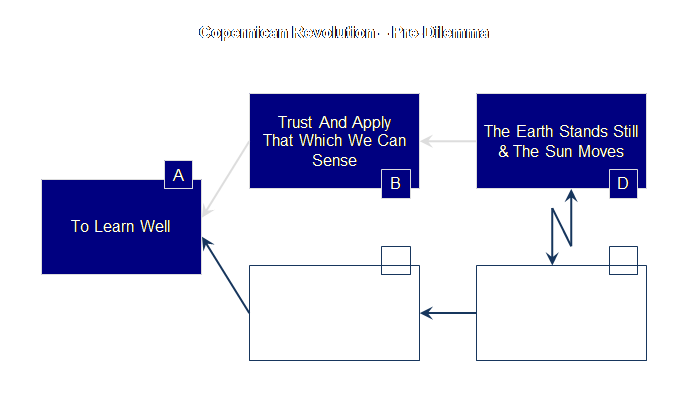

to watch out for it in the following two examples. Let’s start our exploration then with learning and the Copernican

Revolution. For a general

overview of the Copernican Revolution and its technicality, please see Thomas

Kuhn’s (1957) book, The Copernican Revolution: planetary astronomy in the

development of Western thought. This

work precedes his seminal The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by some 5

years. A more recent, delightful, and

thorough treatment of the Copernican Revolution is Dava Sobel’s (2011) A More

Perfect Heaven: how Copernicus revolutionised the cosmos. It has a great deal of the historic

socio-economic context – or should I say contemporary socio-economic context

of that time. It is a kind of story

behind the story, and the tacit nature of paradigm is imaginatively

illustrated but that is all that I will tell you. It is very

hard for us today to imagine a world in which the size of and distance to the

sun, or any other celestial body, was unknown, unimagined, and

unimaginable. The earth was viewed as

the center of the universe and surrounding it were a series of fixed (solid)

spheres containing the various known planets or wandering stars; the Sun, the

Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Neptune, all moving against

the “fixed” stars of the firmament.

The system of astronomy, instrument-based naked-eye observations, was

used as much for fixing and understanding both past and future happenings on

earth via astrology as for the understanding of the cosmology. There was a strong prevalence even amongst

Copernicus’ closest confidants that the stars preordained one’s future and

explained one’s past. And such a

system had served admirably for some 1300 years since the time of the ancient

Greeks. We can

summarize the pre-dilemma phase as follows;

Why is it that

a system that had served so admirably for so long, should come under the

inspection of Copernicus? In part the

answer to that was to seek greater predictive accuracy, the heavens of that

time were the pre-mechanical clock of the world, and in part it was to remove

the pesky issue of a mathematical construct, used since the Greeks and called

an equant. The pre-mechanical clock of

the universe, while working well on average, sometimes slowed down and

sometimes speed up, that is predicted events could be out by several days

either way, and in the context of a heaven that was believed to be constructed

of perfect spheres this was a worrying anomaly. There is

nothing wrong with an equant per se but

its use in this circumstance was simply inelegant. It was, for lack of a better word, a

mathematical “fudge” that made the astronomical or rather mathematical system

yield numbers that agreed with natural observation. Copernicus realized that his objection to

the use of equants could be overcome by changing the center of the universe

from the earth to the Sun. The suggestion

that the Sun could be the center of the universe was not a novel idea and had

been mentioned a number of times by Arabian astronomers. In fact, Copernicus goes to some length to

invoke the authority of these earlier astronomers who had argued in its

favor. But his use of the idea to

remove the apparent anomaly of equants was original and in doing so he

created a dilemma that occupied mankind for several hundred years and every

school child since up to a particular age. The full

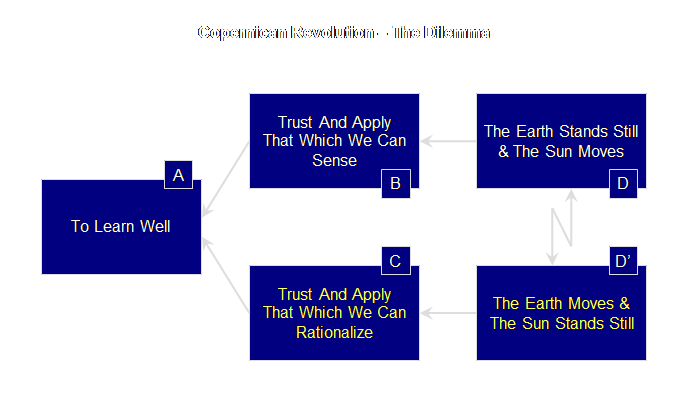

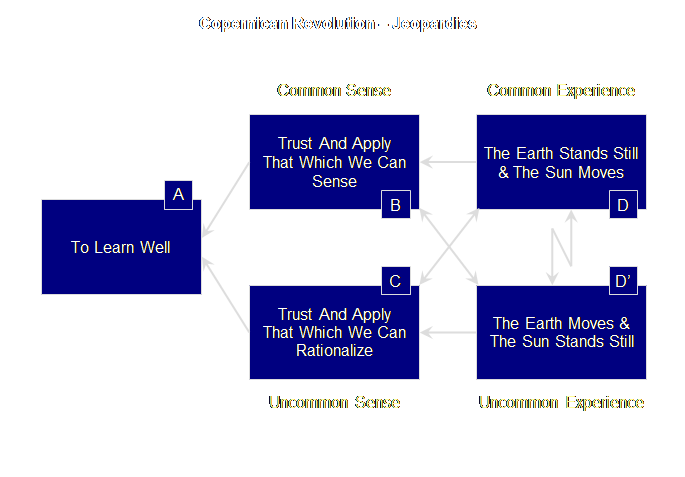

dilemma is expressed below;

Now let’s be careful. This is not to say that the older

geocentric model was not rational, it certainly was, but Copernicus had taken

things to a higher logical level, a different logical type, an abstraction,

something more than we can directly sense.

In doing so he set up a hypothesis that could either be proved or

disproved in the future but maddeningly unprovable at the time. Copernicus did have the satisfaction of

removing equants from his calculations – and thus a more natural description

of the mechanics of the cosmos, but he also had something much more; he had

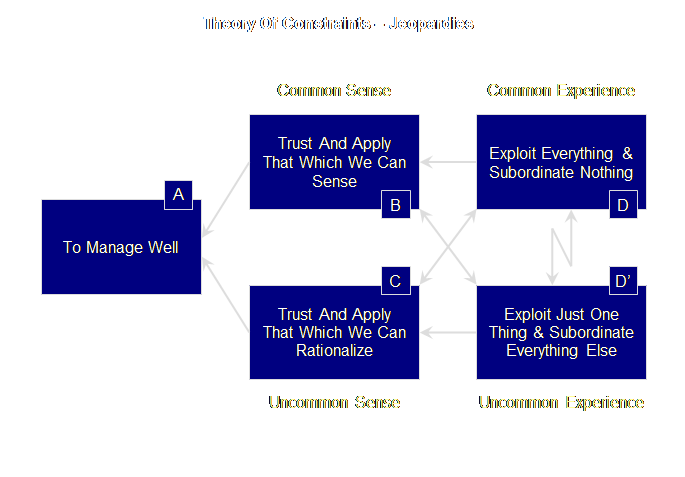

created a new harmony in the heavens. The real issue, however, is not the conflict between

the two outcomes, but rather the contradiction of the senses and of

experience; jeopardies in fact. Let’s

have a look at these;

If common

sense jeopardizes the gaining of and new uncommon experience, and common

experience jeopardizes new and uncommon sense, how then did things move

forward? Was it only the inelegance of

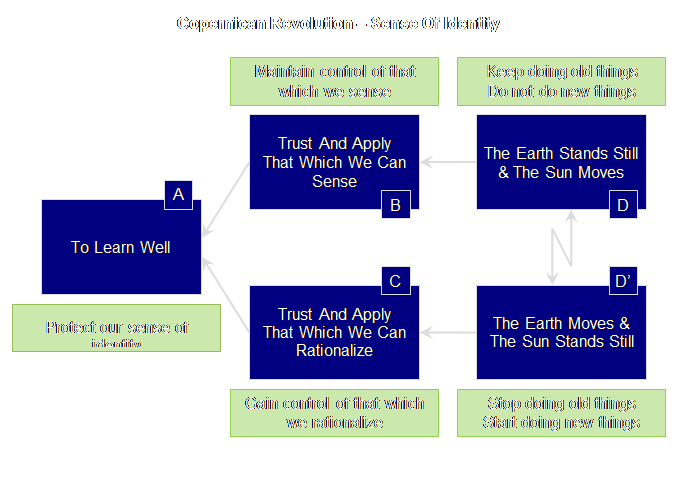

the equant that drove Copernicus to overcome these jeopardies? Well the answer has to be an emphatic no. It is his theology that drove him forward;

his discoveries reinforced his own sense of identity. Paradoxically his passion to prove the

centrality of God, in time, disproved the same. That ironically was never his intent. Let’s look at

this;

Copernicus saw

the Sun as God’s central lantern illuminating his handiwork, he was not the

first to do so, it was a common theme in his

time. Therefore his own sense of

identity as a canon in the Polish Catholic Church was reinforced by his

hypothesis, he was therefore willing to stop doing old things and to start

doing new things, in order to gain control of that which he had

rationalized. His belief and his faith

were one and the same; he had an heuristic passion,

a passion to discover and to learn for himself powered by his faith. He and other mathematical astronomers found

great harmony in the idea of a heliocentric – a sun centered – universe once

it had been proclamated. It redoubled

their faith. For others the very

rock-solid centrality of man and earth and God and the authority of the

scriptures was brought into question and it was viewed as an attack on that

very same faith. The sense of loss of

control for those that had relied upon their senses must have been

profound. It is the two sides of this

dilemma built around our own sense of identity that kept the dilemma open for

so long. One cannot find new evidence

if one is not willing to venture past the jeopardies. Copernicus’

book De Revolutionibus has been described

as “the book that nobody read.” But

Owen Gingerich of Harvard University tracked down 277 copies of the first

edition and 324 of the second. Finding

Kepler’s copy (with the word “ellipse” inscribed by the previous owner in

answer to Copernicus’ concern for epicyclets producing non-circular orbits),

and Galileo’s copy, he decided, that everybody

had read it so to speak. Some copies

going from generation to generation contain annotations in two or three

different hands (Sobel 2011). The outcome of

Copernicus’ rational approach is a unique solution that is independent of place, that is regardless of where we sit in the Copernican

Universe (solar system), we can tell what is happening and

predictively what will happen in the future.

It is this harmony that spoke directly to the

astronomer/mathematicians of the time and those who were to follow. However, for the practical astronomers of

the time Copernicus’ system was neither appreciably simpler nor more

accurate. During

Copernicus’ life-time and for some time thereafter, his ideas remained as

hypothesis, unsubstantiated by any external data. Guided by the harmony that was implied,

Galileo, Kepler, Newton and others found and built productive new

science. However, it wasn’t until 1838

that parallax measurements on nearby stars were accurate enough to determine

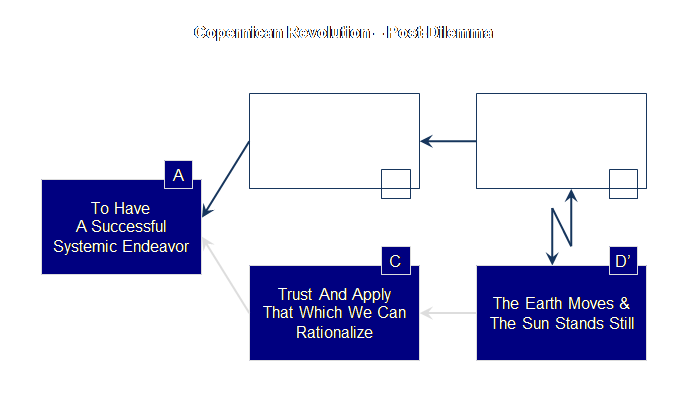

that the earth did indeed revolve around the Sun. Today when we

talk about this dilemma it is often about the contradiction of the senses,

but there is a much richer story, and the underlying lesson is that for us,

rationality must finally win out. As Polanyi

(1958) explained; “We abandon the cruder anthropocentrism

of our senses – but only in favor of a more ambitious anthropomorphism of our

reason.” Let’s have a look at the “modern” post-dilemma

cloud;

We no longer live the

dilemma, the conflict, the contradiction.

And those that did at the time lived it as much as reinforcing their

insider view – which ever side that might have been – and disproving the

complementary outsider view. Rather

today we “switch” views as required.

For the most part we operate as pre-Copernicans, in as much as we fail

to abandon Sunrise, and Sunset, but also acknowledge and accept the

post-Copernican rationalization. There

are very few of us who have become astronauts and they alone are the ones who

have directly experience what for the rest of us is an exceedingly rare

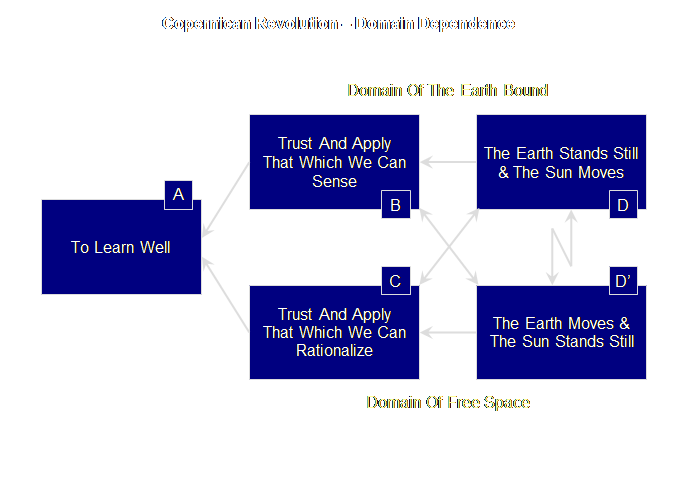

rather than uncommon experience. Why is there a paradox, why is there a dilemma? The first part of the answer is that there

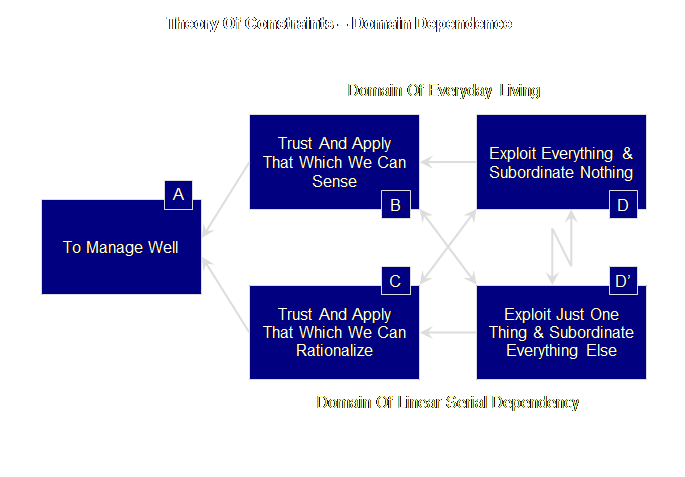

is something in our rationality that contradicts our senses. But what is it? I’ve often called it domain dependence, but

in reality it is a failure to recognize an error of logical type. The rules that apply under the logical type

of our senses do not tell us, and in fact can never anticipate, the rules

that apply under the higher logical type of our sense of senses, our

rationality.

Almost none of us, astronauts excepted, ever venture

into the larger domain of larger logical types and therefore we never worry

too much about the duality of what we sense and what we know. We switch

between the two as need be. And with

that thought, and with some logic, and structure, and understanding under our

belts, let’s now turn our attention to Theory of Constraints and managing our

modern industrial invention, the linear serial dependency, for it is the same

story. Theory of

Constraints is used here as a proxy for all systemic endeavors, not just

Goldratt, but also for Taylor, Shewhart, Deming, Ohno, and Ackoff. These are people for whom the whole was

more important than the parts, and for whom the parts did better for being a

part of the whole. Managerial hierarchy isn’t new, it has existed in

the church, the army, the state, and in various admixtures of the three, at

various scales for maybe 10,000 years or more. But managerial hierarchy within industrial

process is new; it didn’t exist prior to the early 1850’s even in the largest

cotton mills of the time. These

systems employing up to 300 people, still had supervisory foremen who were

workers themselves (Drucker 2006). Up until this

time the pre-dilemma world looked something like this;

In fact, even

today, we (erroneously) know that everyone needs be busy most of the time

(except maybe of course for ourselves), because if they were, then we wouldn’t

have to wait for people upstream to produce the things that we need and we

wouldn’t have to wait for people downstream to be able to receive the needed

things that we have already produced (or be complaining about the new or

different things that they now, suddenly, want produced instead). Except, of course, if we change departments

or positions, and find that now our old department or position is as much a

part of the problem and our new department or position no different from our

experience before. Such analysis shows

a host of non-unique solutions that are each place dependent. Let’s look at

this in another way. We all know that there are folks in the place who are less

effective than they could be, but we are certainly not one of those. However, the same question to each person

yields the same answer. The positional

or departmental viewpoint is a non-unique solution and it is place dependent. We still see this pre-dilemma played out

every time an individual in a group is “reviewed” or “appraised” as an

individual, and rewarded or otherwise as a consequence. We see this pre-dilemma played out in the

Western thinking of worker “compensation” where bonuses demonstrably harm the

system if not the individuals concerned and yet we fail to understand why. Why did this pre-dilemma paradigm last so

long? It lasted so long because as one

moves down the managerial hierarchy, especially pre-industrial hierarchy,

there are more and more individuals doing the work, and more importantly,

they become more and more independent of one another – usually by virtue of

geographic separation – think again of the church, the state, or the

army. The further down the hierarchy

the greater the independence, the greater the ability for local exploitation

to work, or to appear to work. So what changed? Well, let’s have a look. Much has been

made of specialization, but specialization is nothing special. There have always been shepherds, shearers,

fullers, spinners, dyers, and weavers; specialities if not characterized by

age, or gender, or seasonality alone, then certainly by skill and

experience. Ridley (1996) notes the

number of different items found on the 5000 year old mummified remains of a

Neolithic man found in the Tyrolean Alps in 1991 – all products of division

and specialization of labor. And he

goes on to note the “non-zero-sumness” that this achieves; that is, society

can be greater than the sum of its specialized parts. What has

changed is the co-location and lock-step between the specializations and

indeed within any single specialization as mechanization and

industrialization has brought about technical and economic efficiencies that

were beyond the imagination of prior generations. In the terminology of Ackoff (1981/1999) we

have replaced muscle with mechanization and more recently replaced mind with

instrumentation, telecommunication, and computation. During the Industrial Revolution we moved

from loose independent networks of craft made-to-fit, to linear serial

dependencies of manufactured made-to-specification. Although absolute variability went down the

relative importance of the remaining variability rose astronomically. As you well know, and many others do not,

it is the presence of variability and not the absence of hard work that

causes the fluctuations in flow upstream and downstream of each and every

point in the system. As fewer and

fewer entities make more and more of the same output better and better, the

dependency between supplier and supplied becomes

greater and greater. That is not a bad

thing at all, so long as it is understood. Goldratt used

the analogy of a chain to describe such a linear serial process – a chain is

only as strong as its weakest link – and for the first time ever we had a guiding

principle for where to focus our improvement activities and more technically;

where to schedule back from, and also where to schedule forward to. Previous systems did not offer that

simplicity because they all attempted to; manually at first, electronically

later, schedule everything everywhere all of the time. And the advent of electronic computational

power only further fooled us that it was technically possible to do so, even

though we had never asked if it was technically desirable, faith in the old

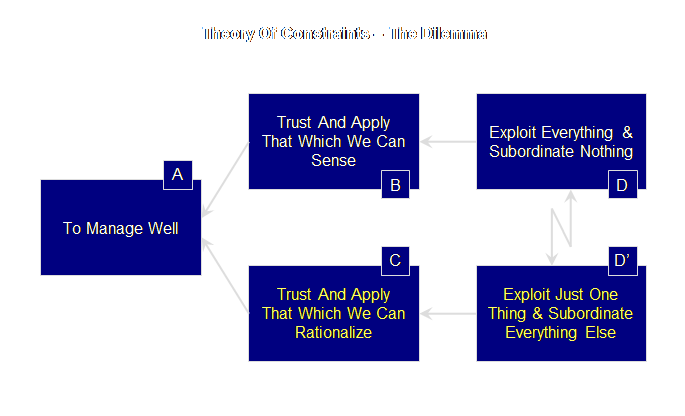

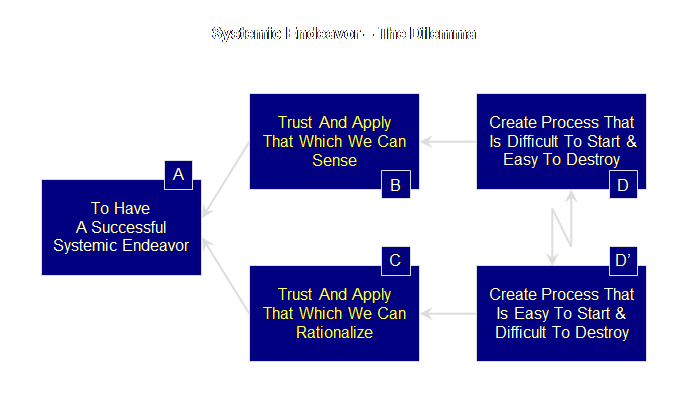

paradigm of keeping everyone busy drove us on to do it without forethought. So Theory of

Constraints and especially the scheduling system called drum-buffer-rope

presented a dilemma within which we are still largely immersed. It looks like this;

Sure, Taylor

(1911) in his introduction talked about the system rather than man and

implied man must subordinate to the system (“In the past the man has been

first; in the future the system must be first). Deming (1994) talked about the obligation

of a component, but that can be too easily read in the old paradigm of “obligation

to do something” whereas here for the first time it meant “obligation to do

nothing” albeit from time to time. The

issue was somewhat further confused by Goldratt’s use of the term Road Runner Ethic. I am told that Real Road

Runner birds in their native habitat (and the cartoon rendition too) run at

great speed and then stop dead still.

But that is always their normal speed.

However, it lost something in the translation and again it seemed for

many people that we were being asked to behave in the old paradigm of working

harder and faster, albeit for shorter periods with more frequent breaks. Nothing is further from the truth, but the

mis-understanding, indeed the mis-appropriation of the old paradigm for the

new, is still apparent. The cliché

from Taylor’s time of working smarter not harder seems a pipedream for many,

it should not be, it is the only way forward. Once again, the real issue is the contradiction of

our senses and of our experience; jeopardies in fact, rather than the

conflicts between the outcomes. Let’s have

a look at these;

Looking at the

other diagonal, the common experience of being “busy” or at the very least

appearing to “look busy” has literally been beaten into us. Deming said “drive out fear” and I think

that he knew a thing or two. Of course

we hide our productive capacity so that we can respond as quickly as possible,

but it is a delicate balancing act.

Fear has been so well beaten into us that it contradicts and

jeopardizes our ability to rationalize the skills and knowledge of the

uncommon sense needed to operate within the new paradigm. Taylor said as much in 1911 when he rued

that people failed to follow the essence of his methodology, opting instead

for their incomplete and wrong interpretation of the mechanics. Liker showed that the Western

implementations of Toyota’s philosophy have suffered a similar fate. Why, why, why,

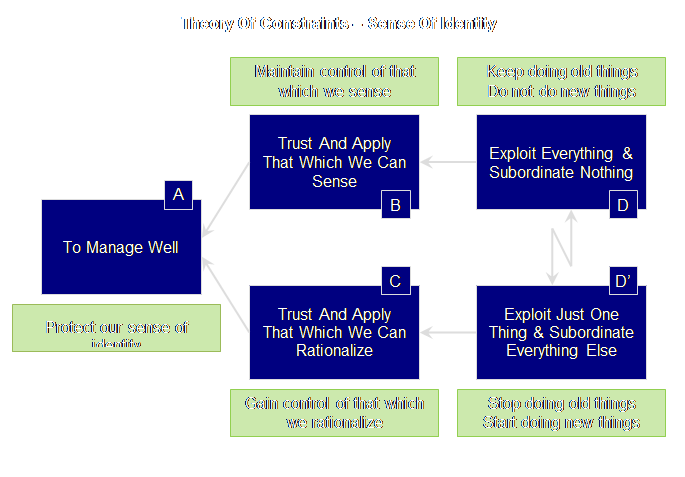

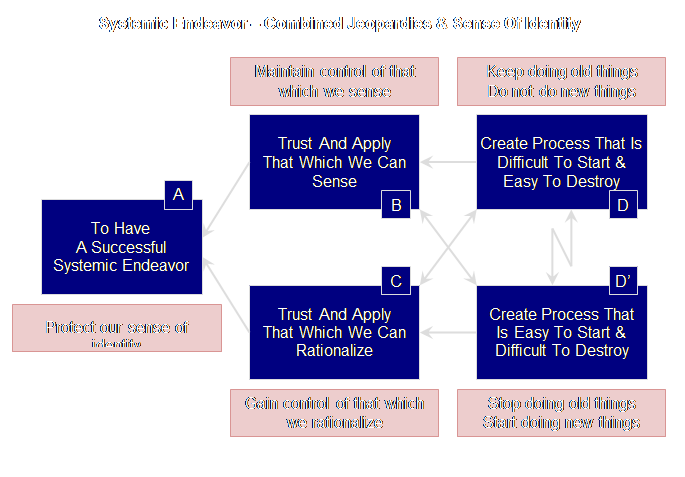

is this? The answer to

a large extent lies within each and every one of us and our own sense of

identity. Let’s have a look;

But all is not

lost. There are others for whom the

rationalization – the uncommon sense – put forth is sound, they can see the

evidence of success in other situations, or even in the abstract, and they

take the time to learn and internalize the necessary new knowledge. Frankly they are “big enough” for the job

or they are well supported from higher up within the organization, which in

fact means the same thing. Their sense

of identity will grow around the new knowledge and they will want

to stop doing old things because this now makes new sense to them, and they will want to start doing new things because this too makes

new sense to them, and they will move

forward. Sense of

identity is a metastable product. Many

of us cling to the old one well after its use-by date, some of us never

relinquish it, many though will “cross-over” at some stage, the more that

have already done so, the more likely the laggards will follow. And of course, later on, newcomers don’t

even see the issue. Just think, once,

not so long ago, large inventories were an asset, nowadays they are more

likely, much more likely, to be viewed as the opposite. The world has moved on, but we did not get

there overnight – not all of us that is – but at some stage the metastable

sense of identity around inventory as asset switched over and became

inventory as liability. Rather like

Copernicus in search of the centrality of his God and inadvertently removing

that centrality, Goldratt’s own search for the centrality of the weakest link

has inadvertently removed that weakest link.

Goldratt moved the world from treating each and every link as

exploitable, to only 4 or 5 in the earliest algorithms for OPT (Optimsed Production Technology), to just one in drum-buffer-rope,

and finally none at all in simplified drum-buffer-rope. Conversely, the role of subordination

increased from almost nothing to essentially everything. “A chain is as

strong as it weakest link” was a pre-paradigmal expression, it owes more to the

past than to the present. In fact a

chain should have no weak link, all the links should be demonstrably stronger

than the environment in which it operates.

We are so unused to thinking like this that we fall back to our

pre-industrial idioms with ease.

The outcome of

our rational approach is a unique solution that is independent of place; that

is, regardless of where in the process we sit, we can tell what the output is

and predictively what will be the output in the near future. And let’s be quite sure, the output will be

very much greater than anything before. Post-dilemma,

there is no conflict;

Our

rationality gives rise to a harmony, an inherent simplicity, which to my mind

leads us into many other areas of fruitful endeavor which we have hardly

begun to scratch yet. Accounting, or

rather decision making springs to mind.

The same principles have already had a major impact in the areas of

project management, distribution, service operations, healthcare, sales, and

strategy. Many, many, people forget, or indeed have

never known, about one of Goldratt’s necessary conditions for on-going

improvement; that of “provide

employees with a secure and satisfying workplace now and in the future.” It’s the antithesis of the Anglo-American

Social Darwinism of the upper arm of the dilemma, it humanistic in fact,

ultimately it is systemic, it is the form of the post-dilemma cloud, and this

is the direction of the solution. We can

summarize all that we have said mechanistically as; A chain must be stronger than the use it is put to Or more

ecologically; A process must be more capable than the environment

that it operates in Again we must ask why is there a paradox, why is

there a dilemma? And again the first part

of the answer is that there is something in our rationality that contradicts

our senses. But what is it? Once again there is domain dependence, but

in reality it is a failure to recognize an error of logical type.

Much as in the Copernican case we moved away from

being small independent “wholes” to being a “part” of a much greater

interdependent whole. In the larger

scheme of things few of us venture into the domain of these wholes – linear

serial systems – and even fewer of us are asked to manage them in stasis, let

alone improve them. Many, many people

work as individuals, or like individuals, in trades, professions, and

domestic situations. More importantly,

unlike the Copernican case where we can switch freely between the two domains

because one domain is essentially abstract to us, here we fail to switch between

the two even though, or even maybe because, we can move so freely between

them. They look so similar we fail to

recognize the transition. How to switch, and it can be done, is the central

issue of the paradox of systemism.

We’ve visited the problem already, not once but twice, let’s now

return to that problem and solve it once and for all.

Now that we

have journeyed through the Copernican Revolution and through Theory of

Constraints, let’s return back to our original issue, the paradox of

systemism, this is the paradigmal issue that we need to resolve. Here is the modified cloud that we started

with;

The answer

should be familiar to us now; it is the contradiction of our common sense and

our common experience, and the way that this also jeopardizes our sense of

identity. Let’s roll this together for

the first time; we have in the same diagram both the need to protect our

sense of identity and the jeopardy arrows as well;

This tacit and explicit subdivision was my original

basis for subdividing B and C in these clouds; however, they are more of the

nature of a continuum than discrete subset and set. Nevertheless, they are also a powerful

dichotomizing tool as well and useful in parsing information into clouds. We have an illusion of knowledge from the upper

arm. That knowledge is correct in the

prior domain of apparent independence; it is our common sense and our common

experience. This is everything that we learnt in life up until trade or

profession including college or university.

Many of us have been examined to hell to through 3-4 or 5-6 or 8-9

years of “higher” education to ensure conformity to these rules. When we port that knowledge to the lower

arm, the newer domain of serial interdependence, that knowledge is now

incorrect for the new application. It

is now indeed an illusion of knowledge.

We attempt to continue to do the wrong thing righter, rather than the

newer and right thing wronger. And if essentially everyone else is also

doing the wrong thing righter too – then how are we to know that everyone is

wrong and that we are seeking smaller and smaller incremental improvements in

our wrongness? The wrongness is

self-validating is it not? This is an error of logical type. The upper arm, our senses, is of a

different logical type than the lower arm, our rationality, our sense of

senses. To paraphrase Polanyi (1966),

the laws that apply to the upper arm are different to the laws that apply to

the lower arm. The operations of the

lower arm, our rationality, cannot be accounted for by the laws governing its

particulars forming the upper arm. That is to say the laws of our rationality cannot be

accounted for by the rules of our common sense. Common sense must be subordinate to

rationality. When we fail to do this

we make an error of logical type. We are told that profound knowledge must come from

outside the system – and it does, but that doesn’t mean we have to re-invent

it every time either. To attempt to do

so would be absurd. The knowledge

exists and it came from outside; physicists like Goldratt and Deming, the

science philosophers of Ackoff, Bateson, Kuhn, and Polanyi, the engineers of

Taylor, Ohno, and the Toyodas. But how

do we get it “in.” And for that matter

how do we get it to stay “in.” There is a double whammy of apparent emotional

arrogance and apparent intellectual ignorance – I say “apparent” because we

are beings of positive intent. Either

“side” of this cloud may be construed by the other to have these

attitudes. Both of these smacks of insecurity because for someone to address these

qualities on either side requires some sort of introspection and the insecure

just won’t go there. Moreover the

insecure will build the virtue of their “side” as a defense against the

“attack” of the other and things quickly build to an impasse (or worse). How then do we

build the security for the introspection?

How do we get past the impasse?

And the answer is that there are two complementary ways which are path

dependent; one tacit and one explicit. We should

start with the tacit first and we should start with ourselves – those of us

who are reading these pages and leading others. A tacit experience breaks in an instant the

paradigmal contradiction. Once broken

it can’t be glued back, we cannot un-know what is now known to us as a new

experience. We have the luxury of

being able to break our specific paradigmal issue this way. And of course it is playing (not saying)

the dice game that does this. How

often are we tricked by our own knowledge into telling

people about the dice game – but not allowing, or rather not insisting, that

they do it.

We deprive people of a primary learning experience. Think of System Dynamics and the Beer Game;

same thing. Or Statistical Process

Control and the Bead Experiment. Like

the proverbial skill of fork-lift driving, everyone talks about how they can

do it – except that they can’t.

Everyone thinks that they can run a supply chain – until they find

that they can’t even run the Beer Game.

Everyone thinks that they are in control – unitl

they are fooled by randomness. That thing

learnt from the tacit experience of the dice game and its variants is going

to depend to some extent on the skill of the presenter, but it is a wedge,

albeit a very small wedge, in the door of the brain opening up the

possibility of a new and uncommon sense leading onto uncommon expertise. And actually that is all that we need. Sometimes the simplicity is scary and it

plays on our own insecurity, it should not, we should be secure in the soundness

of our fundamental knowledge. And this

wedge leads us to the second part. And

again let’s start with ourselves. We

can’t blame “them” for what they don’t know; we can only blame ourselves for

what we can’t properly explain to them.

Let’s look at the explicit dimension. The cloud is

the premier explicit device for explaining the new knowledge and

understanding around the new found tacit experience. Goodness, we’ve just used it to explain the

“mother of all” paradigmal issues; the Copernican Revolution. And we, those of us on the lower arm, don’t

know too much about what a cloud can do.

If I had to hazard a guess I’d say we know about half of what we

should and practice just a small portion of that. And I hope that I am wrong, I hope that

there is even more to know, because so far it’s a pretty damn impressive

tool. The cloud has

a richness that was previously unsuspected; you will find evidence of this in

the Advanced Section [and two newer webinars at TOCICO]. When I originally wrote the three clouds

used here I didn’t know about these more advanced (actually more simple)

approaches. So, in fact, neither do

you have to know about it, but you will

find it useful. Some people have

reacted against this, others have absorbed it productively. I have to say that I don’t care. I only care about people who want to make an improvement to their lives and to the

lives of others. People who want to but can’t

do. I don’t want to see people trapped

within their current paradigm because of our inability to bring them out of

it. I have used

the 3 different clouds that appear on this page to move people. Firstly the Copernican Revolution,

something that people know of and accept.

An anchor if you like. Then the

Theory of Constraints, something people usually know of in their heart of

hearts but have never thought about before and have yet to accept. This pair of clouds contains all the

conflicts and contradictions mirrored in one another abductively. The third cloud is actually the “shadow”

cloud about our own sense of identity, the need for control, the want to do

or not to do, and it really brings all of the issues home. It is very seldom that people are faced

with such honest introspection. It has

to be handled with sensitivity. It has

to be handled with consummate skill. That is the

way that we break the paradox of systemism.

That is how we take something that was previously difficult to start

and easy to destroy and make it easy to start and difficult to destroy. And we are just starting on this journey. Let me leave you with this thought from Frederick

Taylor in 1911; The history of the development of scientific management up to date, however, calls for a word of warning. The mechanism of management must not be mistaken for its essence, or underlying philosophy. Precisely the same mechanism will in one case produce disastrous results and in another the most beneficent. The same mechanism which will produce the finest results when made to serve the underlying principles of scientific management, will lead to failure and disaster if accompanied by the wrong spirit in those who are using it. Hundreds of people have already mistaken the mechanism of this system for its essence. Mistaking the mechanism for the essence is an error

of logical type. We must learn to stop

doing this. Ackoff, R.L., (1999) Ackoff’s Best: his classic writings on management. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp 24-25, originally published 1981. Bateson,

G., (1972) Steps to an ecology of mind.

The University of Chicago Press, pg 314. Deming,

W. E., (1994) The new economics: for industry, government, education. Second

edition, MIT Press, pg 95. Drucker,

P.F., (2006) Classic Drucker. Harvard

Business School Press, pg 181.

Originally published 1988. Goldratt, E. M.,

(1990) The haystack syndrome: sifting information out of the data

ocean. North River Press, pp 11-13. Gould, S.J., (2000) A tale of two worksites, pg 262. In: The lying stones of Marrakech: penultimate reflections in natural history. Vintage, 372 pp. Hofstadter, R., (1959) Social Darwinism in American thought. George Braziller Inc. Kuhn, T. S., (1957) The Copernican revolution: planetary astronomy in the development of Western thought. 24th printing 2003, Chicago, 297 pp. Polanyi, M., (1958) Personal knowledge: towards a post-critical philosophy. Paperback edition 1974, Chicago, pp 4-5. Polanyi, M., (1966) The tacit dimension. Chicago, pg 36. Ridley, M., (1996) The origins of virtue. Penguin Science, pg 48. Sobel, D., (2011) A more perfect heaven: how Copernicus revolutionized the cosmos. Bloomsbury, 273 pp. Taylor, F.W., (1911) The principles of scientific management. 1998 edition Dover Publications, pp iv, 67. This Webpage Copyright © 2013 by Dr Kelvyn Youngman |